I remember as a first-year undergraduate student being incredibly overwhelmed regarding medical school research requirements. Now having had experiences in basic science labs and clinical research, volunteer and paid positions, and a number scientific poster presentations and publications, I hope to share my most helpful tips to help you find premed research and answer some of your common misconceptions.

Learn how to build a compelling medical school application that highlights your strengths and sets you apart from the competition.

Does the type of premed research matter for medical school?

Medical research can be beneficial and easier to incorporate into your essays or personal stories, but it is not inherently superior to research in other fields. You can pursue research in any area, such as psychology, biology, chemistry, physics, and more.

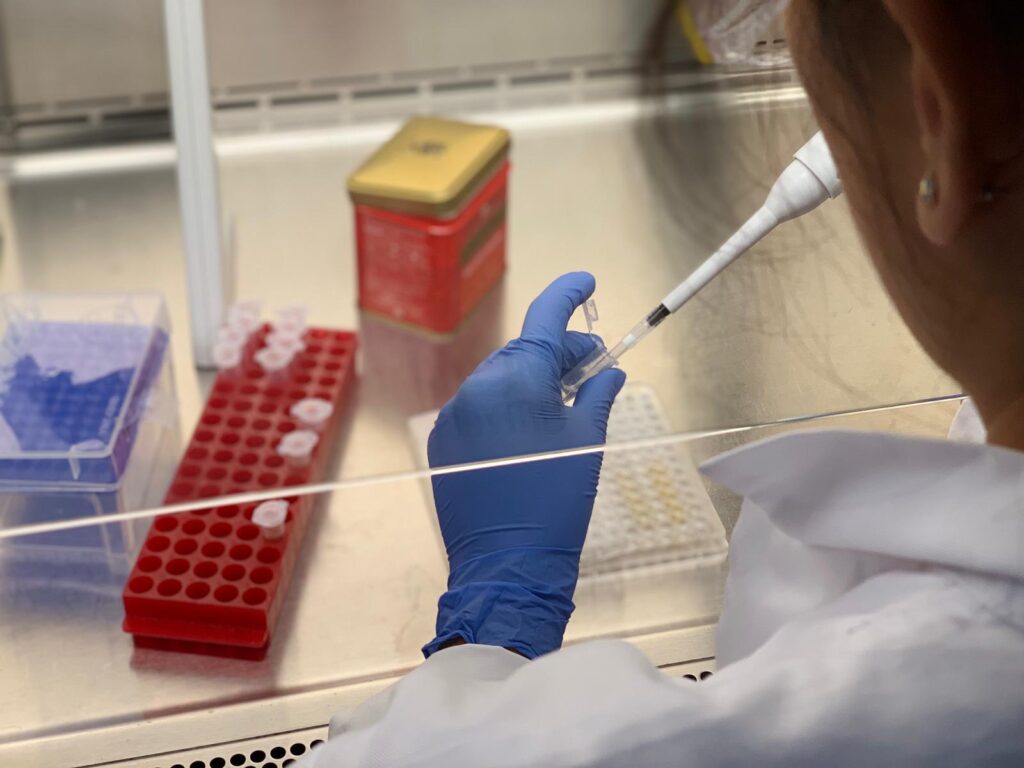

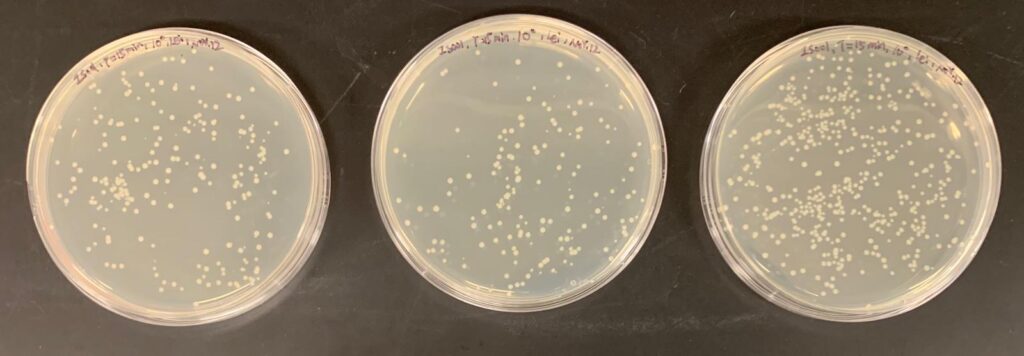

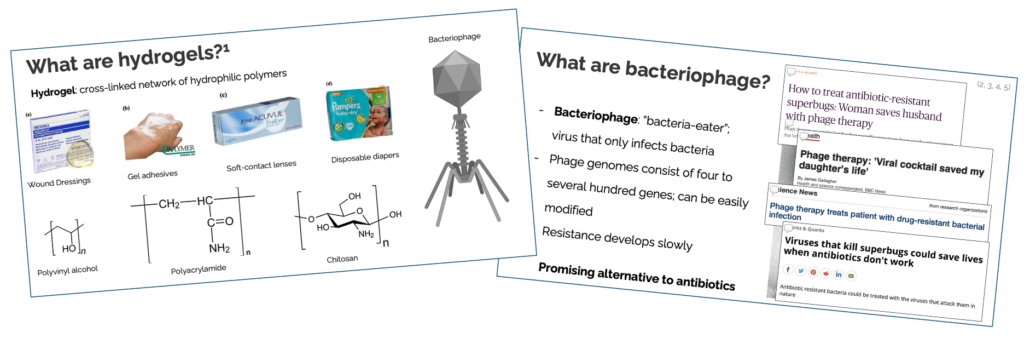

I personally found bacteriophage, microbiology and chemistry interesting, so I pursued research in the intersection of these fields. However, I have colleagues who did research in psychology, polymer chemistry, immunology, etc, who have all received acceptances to medical school.

My advice is to seek research opportunities in fields that interest you and are readily accessible. For example, if you are a chemistry major, it can be beneficial to inquire with your chemistry professors about their research projects to see if there is an opportunity for you to get involved. The specific field of research is less important because, as an undergraduate and medical school applicant, you are not expected to be an expert in medical knowledge or a particular medical field. Instead, engaging in research showcases various valuable skills, such as problem-solving, creativity, diligence, and the ability to understand and generate new knowledge in a field. Demonstrating these qualities through any research experience will positively impact your future application.

Is research required for medical school?

Research is not strictly required, however, medical schools focused on academic output may favour applicants with a heavier research background. MANY medical school applicants will have research experience to some degree. Lack of research on your application should not be the thing that stops you from getting accepted into medical school.

If you truly hate research, I recommend that you either do about 3-6 months of research and aim to create a poster or even get a publication to show admission committees that you can perform research and have acquired relevant skills. Alternatively, you can be honest and skip research altogether, instead focusing on strengthening other parts of your application, such as volunteering and community service.

Find out how to select meaningful extracurricular activities that align with your goals and enhance your medical school application.

How many posters/publications do I for medical school?

Another common misconception is that publications are necessary for medical school. While publications are certainly impressive, they are not essential, and it is by no means detrimental if you do not have one. Publications depend heavily on the field, type of research, and timeline of the research.

For instance, wet lab research (such as chemistry or immunology), often takes a long time to yield publications. I spent over three years in a basic science lab before the projects I contributed to began to be published—over the next 2-3 years after graduating from a lab, I ended up receiving 4-5 publications from my time in said lab. When I applied and got accepted into medical school, I had no publications. To contrast, I was involved in clinical research for a year and received three publications from my efforts.

It is important to pursue research due to your genuine interest in the field rather than merely as a means to an end. If you are not achieving publications, do try to aim for posters, which demonstrates that you are generating results that are recognized by your principal investigator and are presentable to the scientific community.

How do I find research as a pre-med student?

1. Utilize cold-emailing, where you will be sending out tens or hundreds of emails to professors looking for opportunities. Find the profiles of various professors in departments that you are interested in, look at their research topics, and send an email outlining your interest. Quantity over quality for this approach.

Sending emails to a professor that you have never met is probably not something that you would do normally. However, this is an EXTREMELY common way to get research as an undergraduate student. Professors understand that there are lots of students at their university who need research experience. The initial steps would be to check out their university academic profile, check out their lab website, and read some of their recent publications. Then, send an email to the professor introducing yourself. An example template for a student without any prior research experience may look like this:

Dear Dr. X,

My name is (name) and I am a (year of study) undergraduate student studying (subject) at (university). I was wondering if you were looking to take on a (research position e.g. student volunteer, thesis student, research assistant, etc) in your lab.

Having taken (course) and (course) this year, I would love to continue learning and developing a passion for this field. I read some of your recent publications about (topic) and found (XYZ) extremely interesting. While unfortunately I do not bring previous research experience, I have a deep motivation to learn and grow, and I am certain I will quickly become a dedicated, hardworking, and invaluable member of your team.

I have attached my resume and unofficial transcript to this email. Looking forward to hearing from you soon.

Kind regards,

Your name

You might need to email multiple labs to get a response. Even if you do not have prior research experience, that’s okay. Sometimes professors are simply searching for students with excellent grades who can dedicate time towards research rather than someone with prior experience. Shoot your shot!

2. Utilize students who are older than you for research connections.

Getting a research position often is more luck than anything else. You may be the perfect candidate for a lab, but if a position has been filled or a lab is not currently looking for researchers, you’re already out of luck.

Sometimes, the best way to find research positions is to ask older students or to ask your colleagues. Asking your colleagues if their labs have opening, or even how they got their research is a fantastic way to network and will eventually help you find an open research position.

3. Check out your university’s clubs that can set you up with research opportunities.

Your university may have clubs that are specifically tied with research opportunities. For instance, various schools have disease-oriented clubs (e.g. for stroke, cardiovascular health, diabetes) that regularly invite professors to discuss their research. These serve as great opportunities to network, “get your foot-in-the-door”, and meet professors who may be looking to fill positions with students who are already demonstrating interest in their field. Some universities may also have dedicated undergraduate research clubs that are geared towards helping you find positions and connecting you with professors in your field of interest.

4. Check out established summer research programs or awards.

Although they can be quite competitive, summer research programs or awards are a fantastic way to gain hands-on experience in a focused environment. Many universities and research institutions offer these programs or awards to fund research, often designed to provide undergraduates with the opportunity to work on real research projects. These programs typically last 8-10 weeks and culminate in a presentation or publication of the research findings.

Some examples which come to mind include SickKids’ Summer Research (SSuRe) program, University of Toronto’s Summer Undergraduate Research Program (SURP), Sunnybrook Hospital’s SRI Summer Student Research Program, among others.

Often, a professor often is unwilling to take students in unpaid positions due to concerns that you will lose motivation. However, if you find your own source of funding, professors are often very receptive to taking you on as a student. There are broad awards you can apply to (such as the NSERC Undergraduate Student Research Award), or university program-specific research awards that can help fund unpaid research and help you secure a summer research position.

5. Take a research course.

Premed students can effectively find research opportunities by enrolling in student-research project courses or thesis courses. These structured academic courses provide clear goals and timelines, making them more appealing to professors than informal volunteering. Professors are worried that volunteers or unpaid researchers will lose motivation, and thus often prefer students who are committed to a defined project, as it ensures that the research is meaningful and contributes to the student’s academic progress.

Final Thoughts

Though not required, undergraduate research is often an integral and important part of a medical school application. By cold-emailing, networking, applying to structured programs like summer research initiatives, or enrolling in research project and thesis courses, students can show dedication and develop valuable analytical skills that demonstrate an ability to succeed in medicine. I know positions can be hard to find—keep at it, and I promise one will come your way!

Explore our introductory overview of the MCAT, along with essential MCAT study resources and smart budgeting advice to make your prep manageable.